Japonism

Download PDF“When I said that Japonisme was in the process of revolutionizing the vision of the European peoples, I meant that Japonisme brought to Europe a new sense of color, a new decorative system, and, if you prefer, a poetic imagination” (Edmond de Goncourt, Journal, April 1884)

“Japonisme” in the second half of the 19th century, was a craze for everything that came from Japan or imitated its style. The word was first coined in a series of articles published by Philippe Burty, from May 1872 to February 1873, in the French magazine la Renaissance littéraire et artistique. Far from the academic sphere, artists seeking for new ways of expression, appropriated this discovery. Manet and the impressionists led the way to half a century of enthusiasm for Japanese art, and largely contributed to the esthetical revolution Europe experienced between 1860 and the beginning of the twentieth century.

While Japan remained unknown of Europeans for a long time, it appeared in its first mention in The Book of the Marvels of the World written by Marco Polo, as a civilized, rich and powerful island. Even after the Tokugawa government forbade the Christian religion and closed the frontiers of the country in 1639, the relationships between European countries and Japan were never fully severed. Only the Dutch were admitted in the country and they ensured all the commercial ties with the rest of the world from the small artificial Island of Deshima near Nagasaki. The trade of products and ideas was quite intense and filled with curiosity. In 1858, the situation changed drastically. The Unites-States obtained a trade agreement with Japan, and quickly, European countries signed some with Japan.

From 1862, The World’s Fairs provoked massive arrivals of fans, kimonos, lacquers, bronzes, silks, prints and books that launched the real era of Japonisme. With those exhibitions, the demand was boosted, the number of merchants and collectors was multiplied, and artists became passionate about this new esthetic. For them, its “primitivism” was probably its most important quality: artists were fond of the Japanese art’s capacity to be close to nature and to reconcile art and society by representing, with a lot of care, the most trivial objects.

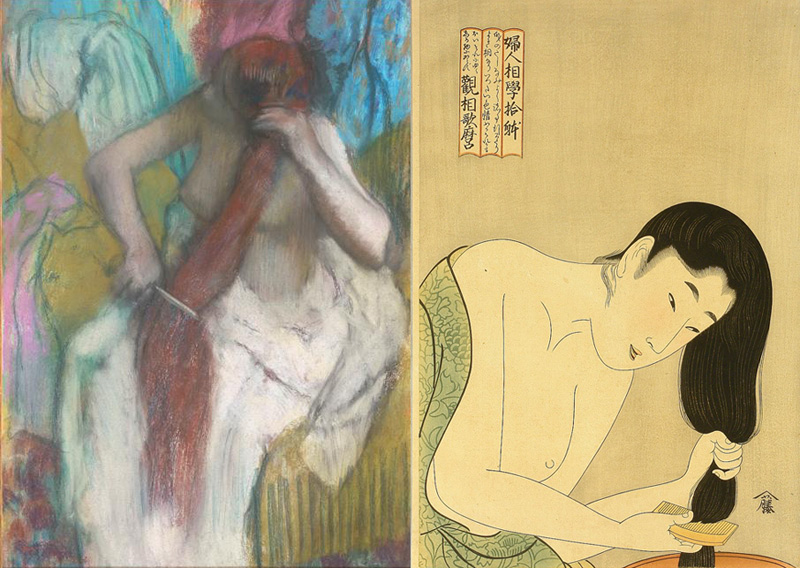

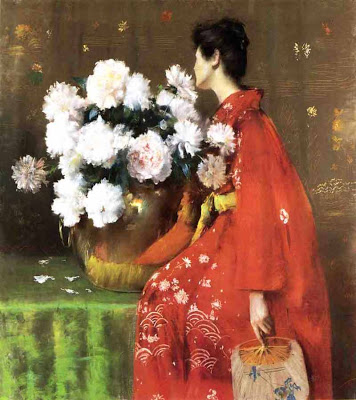

In painting, Edouard Manet, Mary Cassatt, Degas, Van Gogh, Gauguin were among those who were deeply inspired by Japanese art, affected by the lack of perspective and shadow, the flat areas of strong colour, the compositional freedom in placing the subject off-centre, with mostly low diagonal axes to the background. The Japanese iris, peonies, bamboos, kimonos, calligraphy, fish, butterflies and other insects, the blackbirds, cranes and wading birds, the cats, tigers and dragons were endless sources of inspiration, appropriation and reinterpretation for European artists. The occidental productions were combining styles and artistic conceptions instead of copying Japanese art slavishly. That is what brings to light the comparison between the artworks of Kitagawa Utamaro and Degas, of Katsushika Hokusai and Van Gogh (pictures 1 and 2).

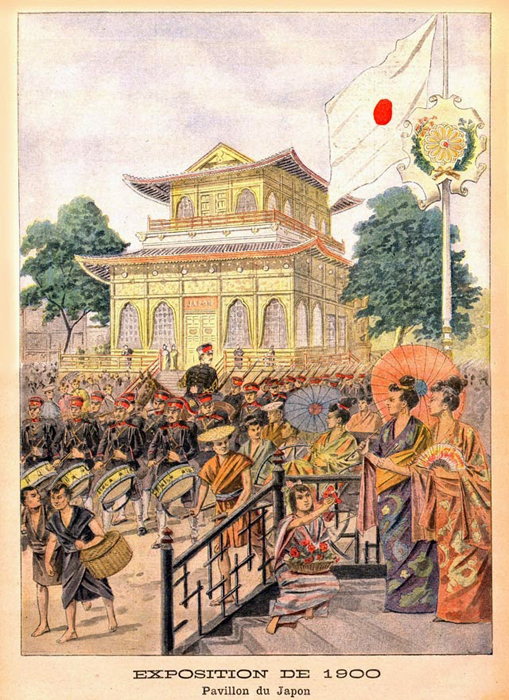

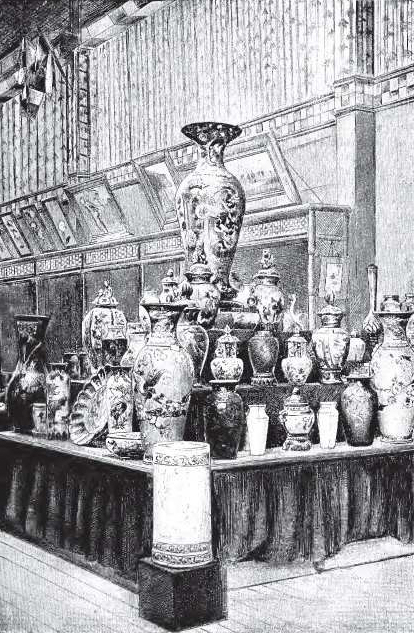

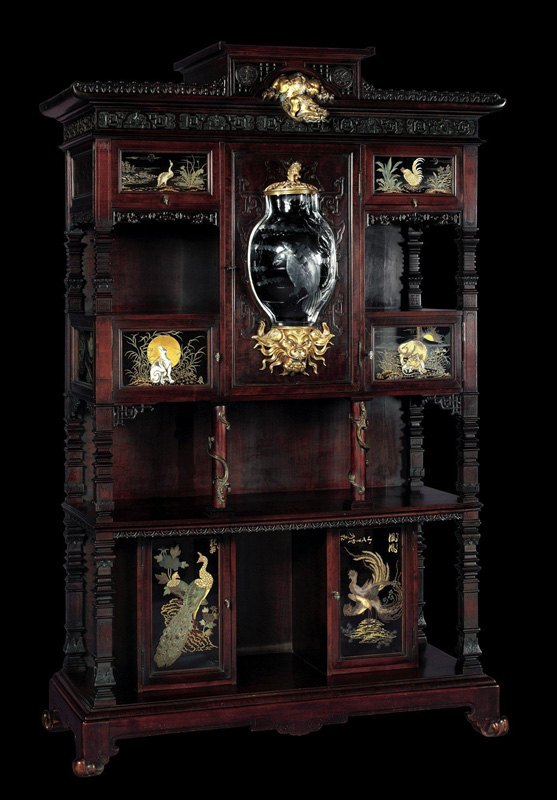

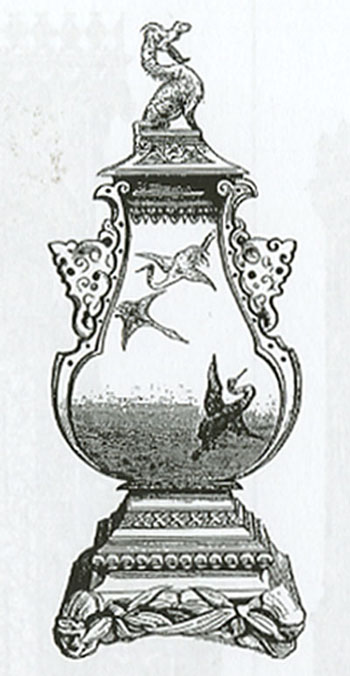

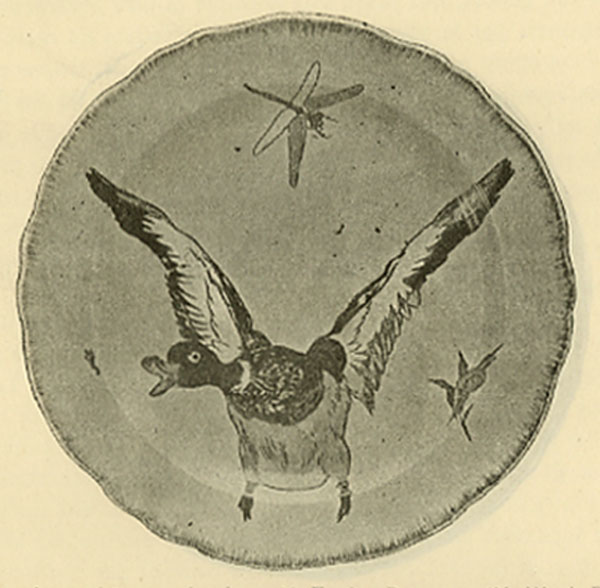

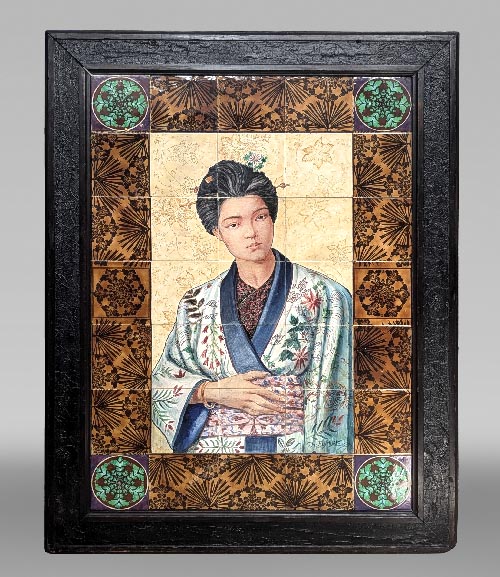

The World’s Fairs of 1851 and 1862 in London, those of 1867, 1878, 1889 and 1900 in Paris, of 1873 in Vienna and of 1904 in Saint Louis presented a number of “Japanese-Chinese” installations with earthenware, bronzes, screens and paintings and attracted the largest amounts of visitors (pictures 3 and 4). In Vienna, the “Japanese village” particularly drew the attention. These were reinterpretations combining elements from Japan and China, mixing them to a degree one could not differentiate between them. Interior design was equally influenced by oriental art, architects showed a keen interest in Japanese houses and furniture. Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Josef Hoffmann and Gustav Klimt were early propagators of Japonisme.

Several cabinetmakers, mostly Parisians, specialized into Japanese furniture. Gabriel Viardot was the leader of those producers, their oldest representative, and the one who had the longest influence. This cabinet (picture 5) well embodies the period and the artwork of the creator.

Another important name would be the one of Edouard Lièvre. The climax of his career corresponded to his Japanese production. While the time was at the “Neo” and at the pastiche, he stood out because of his great creativity.

The Maison Duvinage was renowned thanks- in part- to its patent of invention for a “combined mosaic”: pieces of ivory, fixed on a wood panel, are used for the background, some metal compartmentalizes them, the motifs in nacre are incrusted into the ivory to figure flowers or birds. One of the prettiest example of furniture unit realized with this technic is today kept at the Orsay Museum in Paris (picture 7).

In the field of the objects of art, the boutique Escalier de Cristal , opened at the beginning of the 19th century, had a high production, and enjoyed a great reputation. It collaborated with many craftsmen: bronze makers, cabinetmakers, lacquerware makers and painters who realized numerous decorative objects to adorn the shops (picture 8).

Art Nouveau in France, Arts and Craft in England, Free Aesthetics in Brussels were all movements that were influenced by the Japanese ideal of unity in art. In the late 19th century, art dealer Siegfried Bing, being perfectly aware of the importance of the fusion of art and life in Japan, exceeded Japonisme and launched the Japon Artistique concept in 1888 - art as indissociable with life.

Bibliography

S. Wichmann, Japonisme, Milan, 1982.

1988, exposition Le Japonisme, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais à Paris, Musée national d’art occidental de Tokyo, RMN, Paris.