Napoleon III style

Download PDFLouis Napoleon Bonaparte (1808-1873) was Emperor of France from 1852 to 1870 under the name of Napoleon III. In a way, the artistic codes of the Napoleon III style — also called Second Empire style — were presented at the Exhibition of 1844, during the reign of Louis-Philippe d'Orléans.

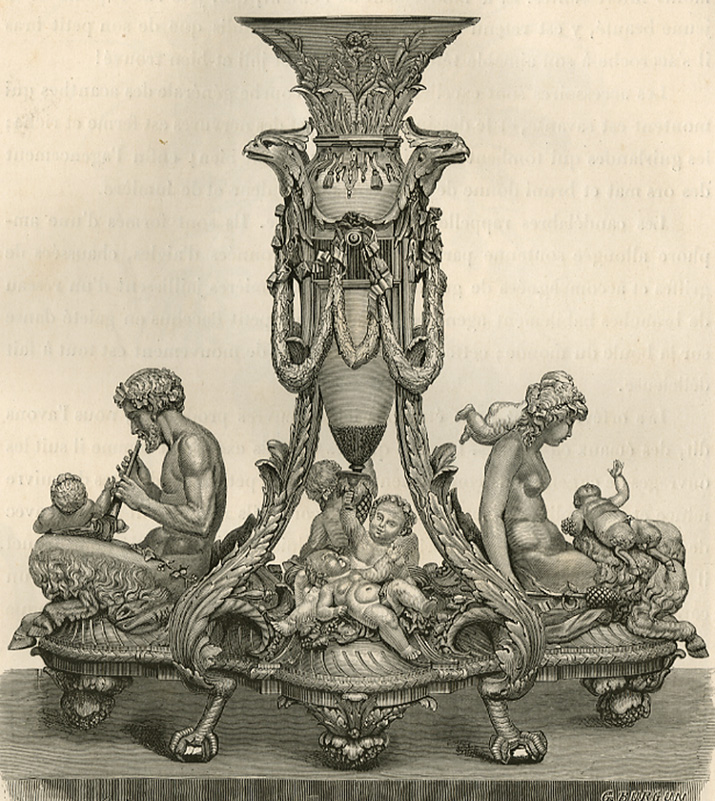

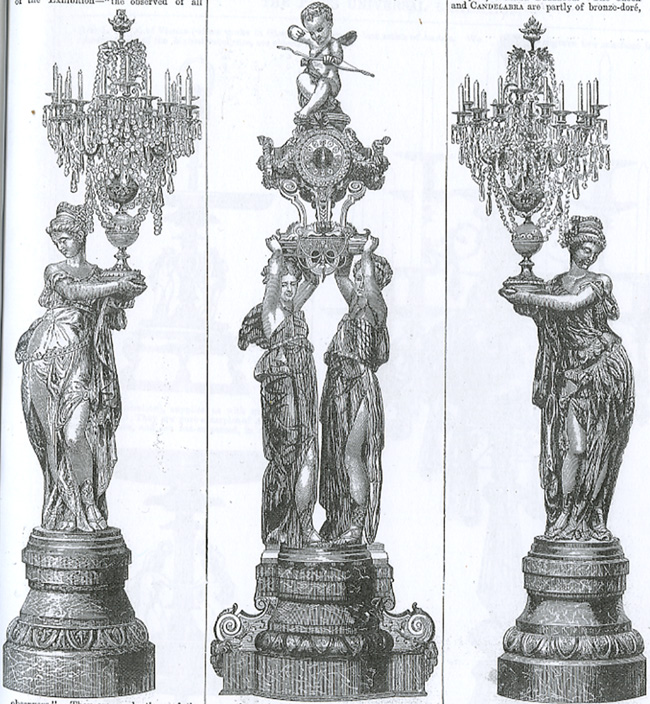

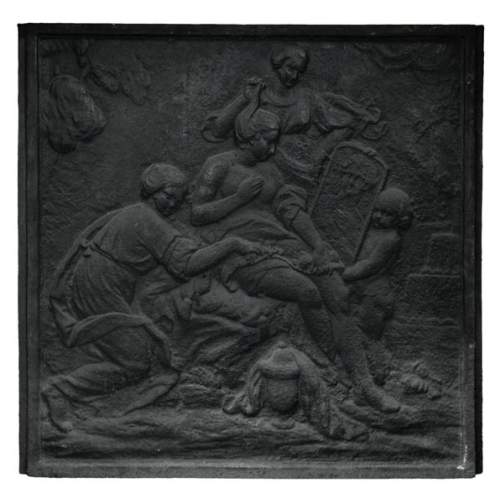

Ornamentation and decoration are the focus points of this period. There were plenty of high-quality furnishings and fabrics. Second Empire designers were renowned for their imposing interior designs. In a room, the focal points were the fireplace mantels, mirrors, candelabras, sconces and chandeliers. The decorative elements used, such as atlantes and caryatids , were synonymous with luxury.

The Second Empire brought recognition to decorative art and artists like the ornamental sculptor Henri-Alfred Jacquemart (1824-1896), the famous metalworker Charles Christofle (1805-1883), and the cabinetmaker Alfred Beurdeley.

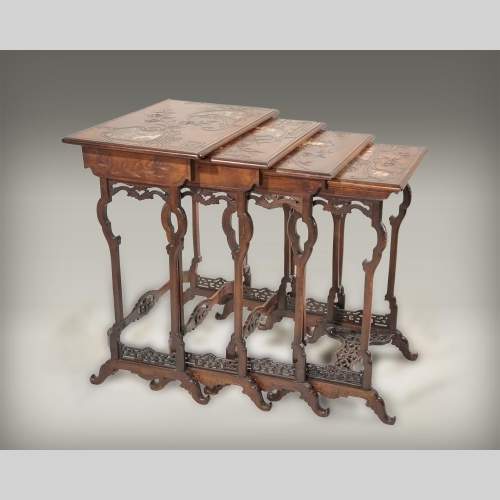

The Second Empire style can be summed up with in one word: abundance. There is an abundance of inspiration, a profusion of materials and a richness of decoration, made up of a generous mix of 17th and 18th-century styles. This period is famous for its tortoiseshell and metal marquetry furniture in the style of André-Charles Boulle, Louis XV and Louis XVI-style living rooms, and Renaissance-Henri II-style dining rooms.

The Louis XVI style or more precisely the furnishings made for Marie-Antoinette set the tone for the Second Empire interiors. The Empress Eugénie, who adored Marie-Antoinette, initiated the resurgence of Louis XVI-style elements such as flower-baskets and tied ribbons. The Louis XVI-Empress-style copied and was inspired by the works of Carlin, Weisweiler and Riesener and was presented to the public at the Universal Exhibition of 1867 .

Important names of the time include Bellangé, Beurdeley (Imperial warrant), Cremer, Dasson, Grohé, Diehl, Fourdinois (the Empress' Warrant), Linke and Sormani. The cabinetmaker Antoine Krieger created “meubles à mécanisme” (furniture with a special, sometimes secret mechanism) inspired by 18th-century furniture. Small side tables on rollers were made as well as black lacquered furniture covered with flower bouquets.

This was the time of French industrialization, progress, and industrial art. The technique for making large tufted cushions was invented in 1838, as well as cast iron furniture that could be reproduced mechanically. This period saw many innovations: new machines allowed for very fine and precisely cut veneer, gold-plating could be used on ornamental bronzes, and marble-carving became easier. The invention of carton pierre (a type of papier-mâché) could be used to produce fake sculpted decorations. The use of electroplating and silver-plating in metalwork, the Christofle specialty, brought high creative freedom and a broader access to products that had up til then been reserved for the very wealthy.

The Second Empire was a period that sought to reconcile progress and innovation with tradition and historicism, a crossroad between a desire to evolve towards a promising future and a lingering sense of attachment to past centuries. This phenomenon is linked to the Romantic “crisis of modernism” of the 1800's.

In general, the Napoleon III style was characterized by exuberant shapes, a profusion of decorative motifs, and rather naturalist human figures, such as those created by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, a sculptor famous for making the Dance figure on the Paris Opera house.

Princess Mathilde, the Emperor's cousin, supported artistic creation during the Second Empire, primarily by collecting paintings. She herself painted watercolors and participated in the Salons held from 1859 to 1897. She held a famous art salon rue de Courcelles, where she received Carpeaux, Marcello, Gavarni, Lami, Doré, Flameng, Roybet, Détaille, and Jacquet. These three last painters were to acquire great fame under the Third Republic.

The State supported the arts by commissioning artists from the official Salon whose work did not shock the eye, placing public and private orders. The former Salon de l'Académie (Salon of the Academy) became the Salon des Artistes français (Salon of French Artists), and at the end of the Empire, the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (Fine Arts Society) was created. In 1863, Napoleon III authorized the Salon des Refusés (a salon for the paintings refused at the official Salon), which illustrated the rise of modernism in painting as opposed to official taste and “Classicism”. The Emperor also supported the Universal Exhibitions during his reign.

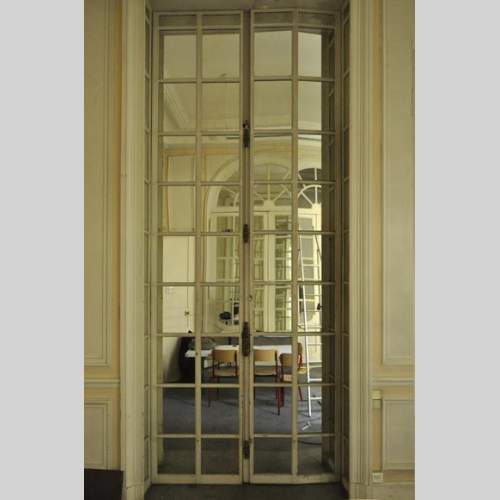

Many monuments were constructed or renovated in different “historicist” or “eclectic” styles, a mixture of European styles from the past. There are for example the Vestibule d'Harlay at the Palais de la Justice (constructed 1852-1868) by Joseph-Louis Duc (1802-1879), reminiscent of Ancient Greek architecture, the “Gothic-style” restoration of the château de Pierrefonds (1857-1879) by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879), the New Louvre by Visconti and Lefuel inspired by Renaissance architecture, and the Opera (1861-1875) by Charles Garnier (1825-1898), a monument inspired by Baroque architecture but also by many different styles from the past, a characterization of “eclectism”.

This period saw the transformation of Paris under the impulse of Baron Haussmann . The creation of investment-property apartment buildings led to a renewal of urban architecture and allowed architects and decorators to freely express their imagination, to the delight of the bourgeois society that was gaining power continually throughout the Second Empire.

The eclecticism of the Second Empire, the association of past tradition with the development of modernism, would be referred to as a “style without style”. The Napoleon III-”style” was in fact more of a combination of different styles from past centuries adapted to the modern era in order to correspond to a time of dynamic, innovative transformation.