World's Fair of 1867

Download PDFAchieving even more wonders than the previous ones, the World’s Fair of 1867, organized by Napoleon III in Paris, is one of the most important World’s Fairs . To bring together 32 countries and their colonies, Napoleon III innovates to "make it more universal than the previous ones", notably by organizing it with national Pavilions, which will remain the formula of the future exhibitions.

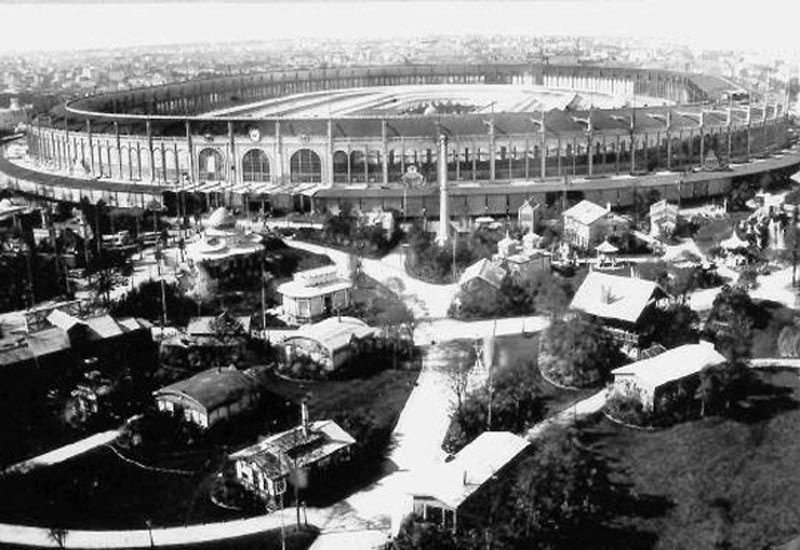

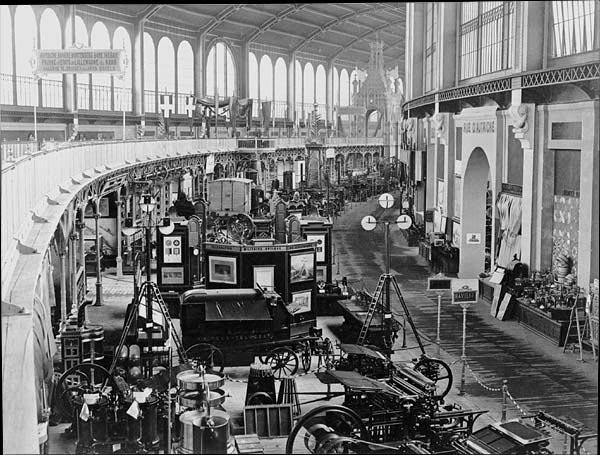

It took place for the first time at Champ-de-Mars and was directly accessible from a train station, it welcomed more than 5,200 exhibitors and 11,000 visitors in a palace built by the architect Leopold Hardy in collaboration with the engineer Jean-Baptiste Krantz. They conceived the Palais Omnibus, a huge circular building where one can admire manufactured products and machines, such as the washing machine or the hydraulic lift of Léon Edoux. The countries invited had each a section, with France, Belgium, Russia and England occupying most of the space.

The ellipsoidal shaped building was made up of eight concentric rings, resembling a double hierarchy. The idea was that the rings were divided into nations. It was a masterpiece that aimed to respond to modern needs of classification. Taking the name of “the Moderm Colosseum”, this building represented the triumph of rationality whilst giving the allusion of strength and productive power coming from the participating nations.

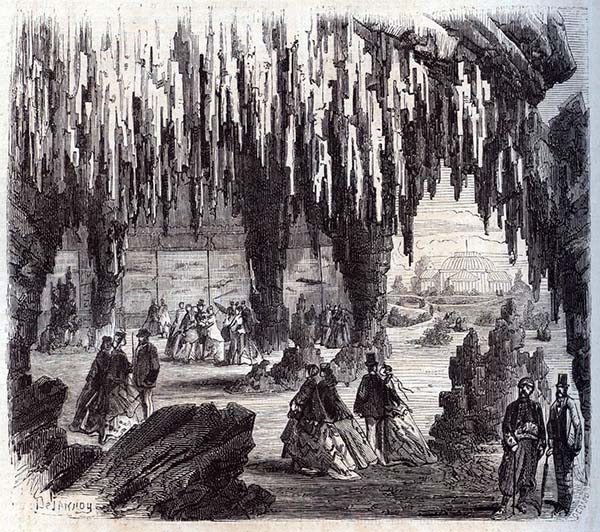

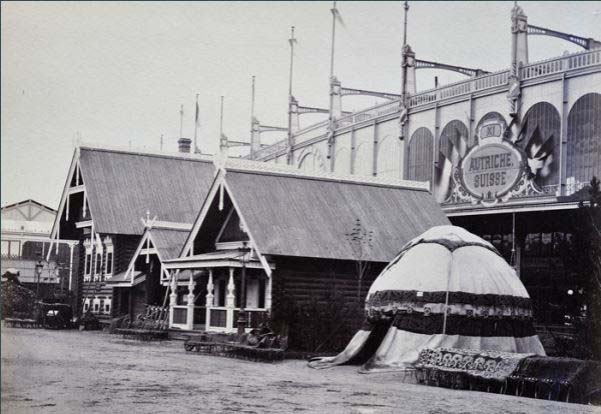

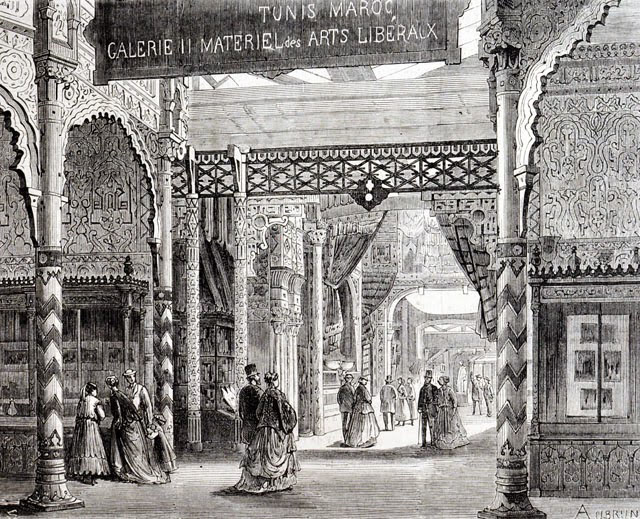

Around the Palais Omnibus, visitors have the opportunity to wander in a pleasant park, another important novelty, where are built the "exposition’s architectures", or national Pavilions. Countries are invited to build on-site ephemeral buildings representing their culture and the beauty of their architecture. New curiosities, these pavilions make the Exhibition a real walk around the world, full of wonder. Mexico thus chooses to build a temple of Xochimilco, the Swiss made traditional cottages, Tunisia realized a reproduction of Bey’s Palace. Other curiosities are also present, such as the Aquarium where a deep sea diver demonstrates this technology by spending several hours in an apartment engulfed underwater.

Last but not least, throughout the Park were restaurants offering cuisine from all over the world, so that the discovery was complete.

Open until 11 o'clock at night thanks to electricity, it was a symbol of modern day progress.

As France’s guest of honor, Russia exposes its rich goldsmith's work in the Palace, while outside it is a whole village that is built. Thus, one discovers there in particular the yurts of Siberia, and the typical Isbas, which charm the Parisian public. In the 16th arrondissement of Paris and at Saint-Cloud, the Isbas from the World’s Fair of 1867 are still in place nowadays.

Egypt also made a sensation, Ismail Pasha having been persuaded to work with the Egyptologist Auguste-Edouard Mariette to create a true cultural manifestation about the treasures of ancient Egypt. Mariette imagines the great Temple of Athor, a building with characteristic features of several ancient temples, and a path lined with Sphinx, which are a highlight of the Exposition. True antiquities are brought to the Exhibition, including mummies, the bandages of which are removed for the event, in the presence of sovereigns, in order to study the antique process of embalming.

Finally, Japan is participating for the first time at the World’s Fair. The event is of great importance for European artists, on whom the art of Japan makes a great impression: the World’s Fair of 1867 hence marks the beginning of Japanism.

In the decorative arts, the cabinetmaker Charles Guillaume Diehl is recognized as the most innovative, with a great medallion cabinet that causes astonishment. Decorated with Gaulish bronze helmets and shields, this great piece of furniture is a curiosity of the Exposition, now preserved in the Orsay Museum.

The Grand Prix is awarded to Fourdinois for a large cabinet of Neo-Renaissance style, adorned with winged sphinxes carved in the round.

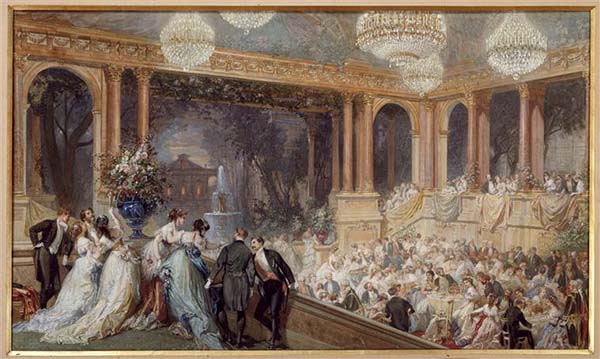

Aside from fine arts- such as painting and sculpting- it was the triumph of an official art, largely criticised by Zola. Meissonnier, Cabanel, and Rousseau were lauded, whilst Courbet and Manet set up independent workshops on Avenue de l'Alma. Having already been noticeable at the World's Fair of 1855 , and once again at the Salon des Refusés of 1863, the gap between academic art and modern dissidents was growing.

The World's Fair of 1867 took place during a period of social and labour struggle. Taking place during a period of contestation in the working world, this exhibition is considered preponderant for three reasons. Firstly it is considered a great retrospective of the history of work. Secondly it was an exhibition that featured products hoping to improve both the physical and moral conditions of the population at the time. Finally it was an exhibition that saw the arrival of labour delegations at the expense of the state. These connections were incorporated in the founding texts of the French trade unionism, and some were enforced in legislation. In a sort of utopia, the state attempted to portray the Universal Exhibition as guarantor of the worker's well-being in social harmony. The nationalist hyperbole of the preceding Universal Exhibitions thus replaced the worry of dispute among the workforce. This reversal of values was a means of appeasing the anger and revolt deep within, which unfolded, the year after, in the Revolution of 1868.