Unicorns

Download PDFThe word “unicorn” dates back to the early thirteenth century, from the Old French unicorne, which derives from the Late Latin uniciornus, the noun form of the adjective unicornis which was used to designate a creature with one horn. Many myths and legends developed around this creature, and it also influenced many artists.

A creature of Asian origin ?

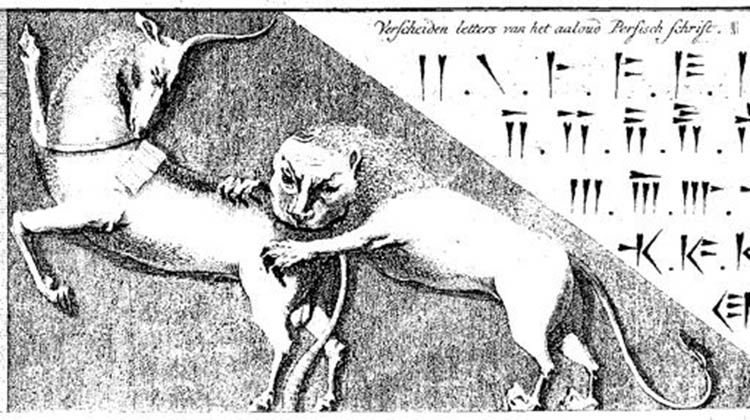

The first traces of this myth seem to have originated in India, Tibet, and Persia. Firstly linked to shamanic fertility rituals and to the moon, they appeared in popular culture early on. In Persepolis, there are low-reliefs representing these animals (see photo 1). An ancient Indian legend about a horned hermit, “Ekasringa”, was spread all over Asia. In China and Japan, these animals are the “Qilin” or “Kirin” (see photo 3) and look more like reptiles and other dragons.

Indian princes are said to have drunk out of carved unicorn horns in order to protect themselves against poison. This is explained in texts from Ancient Greece:

«

“Wild donkeys as big as horses, some even bigger. They have a white body, a purple head, blueish eyes, a horn on their forehead […] They are made into drinking vases. Those who use them are not subject to convulsions, nor to epilepsy, nor to poisoning, […] The Indian donkey is the only one who has them. Their bone structure is the most beautiful I have ever seen; its figure and size are like that of an ox. […] This animal is very strong and runs very fast. Neither the horse, nor any other animal can catch up with it.”

Ctésias, History of India, chapter XXV, ninth century B.C.

A divine, purifying animal

The unicorn's power of purification was very important in the Middle Ages, a time when sicknesses were still greatly unknown. The creature was said to have the power to purify water with its horn and the horn's powder was thought to be the best antidote.

In order to integrate this pagan animal into Catholic culture, it was soon assimilated to a divine creature. In the Bible, there is an animal with one horn called re'em, which is a sort of wild horned buffalo that represents divine power. When translating the word from Hebrew into Greek by the word monoceros (one horn), the descriptions of unicorns were associated to this animal.

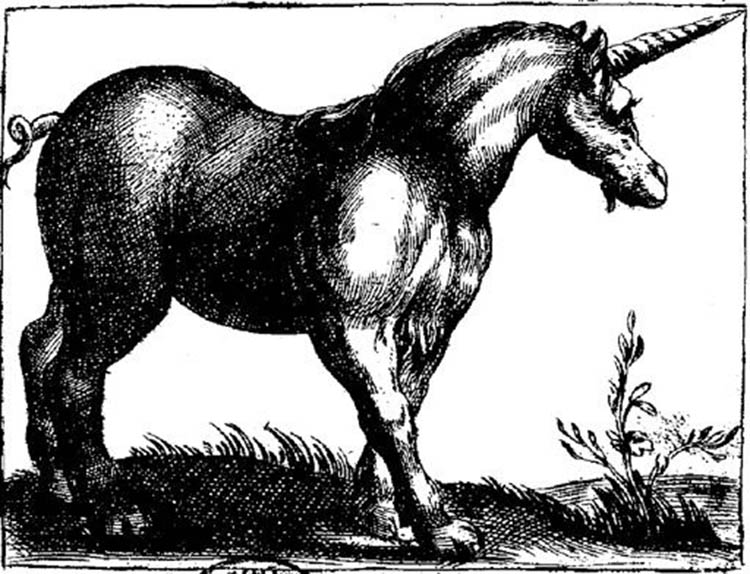

As of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the unicorn invaded the arts. It was represented in the famous illuminated bestiaries (see photo 4), along with the elephant and the lion. It was also represented on tapestries, like the remarkable Hunt of the Unicorn in The Cloisters museum in New York City, and in chants such as the story of the Dame à la licorne et le chevalier au lion (The Lady and the Unicorn and the Knight and the Lion).

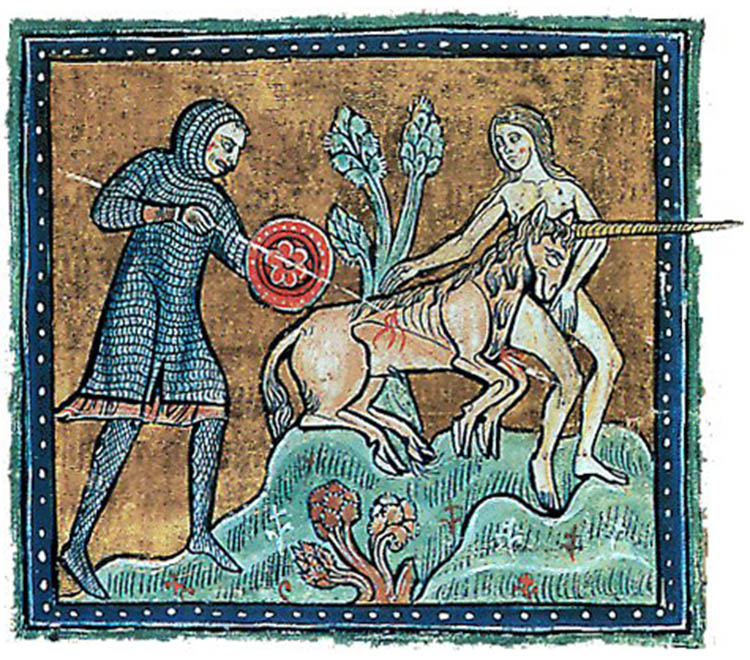

There are many tales about the capture of unicorns (photo 5). The hunt of the unicorn is as dangerous as it is difficult. The beast is described as particularly cruel and extremely fast. Nonetheless, a young virgin, the symbol of purity, can attract the creature that then falls into a deep sleep, making its capture possible. A comparison was made between this noble, pursued animal, and Christ the Redeemer: “a heavenly unicorn that descended into the breast of the Virgin.”

« “As monoceros or unicornis has the shape of a young goat with a horn in the middle of its head, so ferocious that no man can catch it, except by bringing a young virgin to the place where the unicorn lives and by leaving her alone in the woods, sitting on a chair. When the unicorn sees the young girl, it falls asleep on her knees, the hunters seize it and lead it to the palaces of the kings.”

Pierre de Beauvais, Bestiary, thirteenth century.

Cabinets of curiosities

Cabinets of curiosities, a cross between the apothecary's cabinet and a collection of artwork (photo 2), were highly coveted throughout the Renaissance. Unusual, intriguing objects were collected and sometimes given magical powers. Amidst a rock-crystal, a bezoar stone, and Roman sculptures, it was not uncommon to find a unicorn horn, especially in a prince's collection. These objects were kept as relics, adorned with precious settings. They were rare and precious, which made them very expensive.

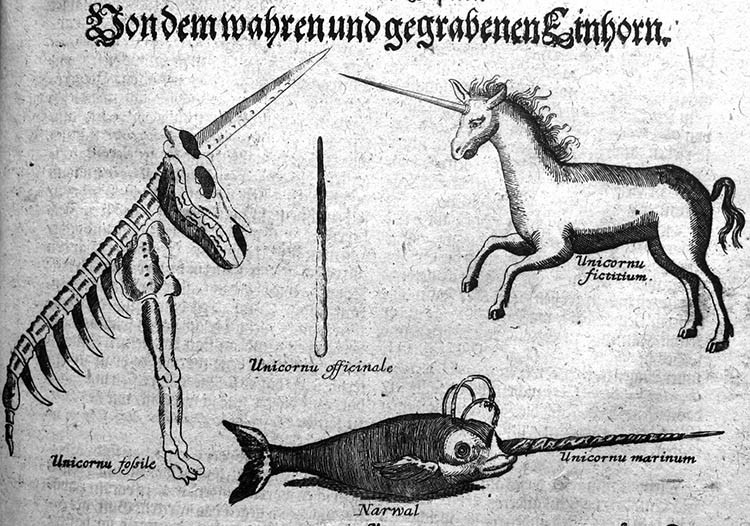

The Caliph of Bagdad Haroun-al-Rachid gave a unicorn horn to Charlemagne as a diplomatic gift in 807. Today it is kept at the musée de Cluny. The inventory of the Medicis' cabinet of curiosities mentions that a unicorn horn was worth 6,000 florins, when a Van Eyck was only worth 30. These horns obviously did not really come from the mystical creature, but from narwhals. Rare at first, the expansion of navigation methods made the object trite and its worth collapsed. The secret was completely uncovered at the seventeenth century. This did not stop the king of Denmark from building himself a “Unicorn Throne Chair” made entirely from narwhal and walrus horns (photo 7).

The Nineteenth century: the medieval and Renaissance fashion brings back the unicorn

During the nineteenth century, from the start of the Restauration, artists had a new-found interest for the times of the Kings of France. They rediscovered illuminated manuscripts, tapestries and heraldry featuring the unicorn. The Musée de Cluny was inaugurated in 1844, and artists rushed to this museum in search of inspiration. In 1882, the curator, Edmond du Sommerard, acquired the Dame à la Licorne (The Lady and the Unicorn), a series of six tapestries woven in Flanders between 1484 and 1538 (photo 14). The many interpretations of this mysterious piece influenced a whole generation of writers, especially the Symbolists, led by Gustave Moreau (photo n°9).

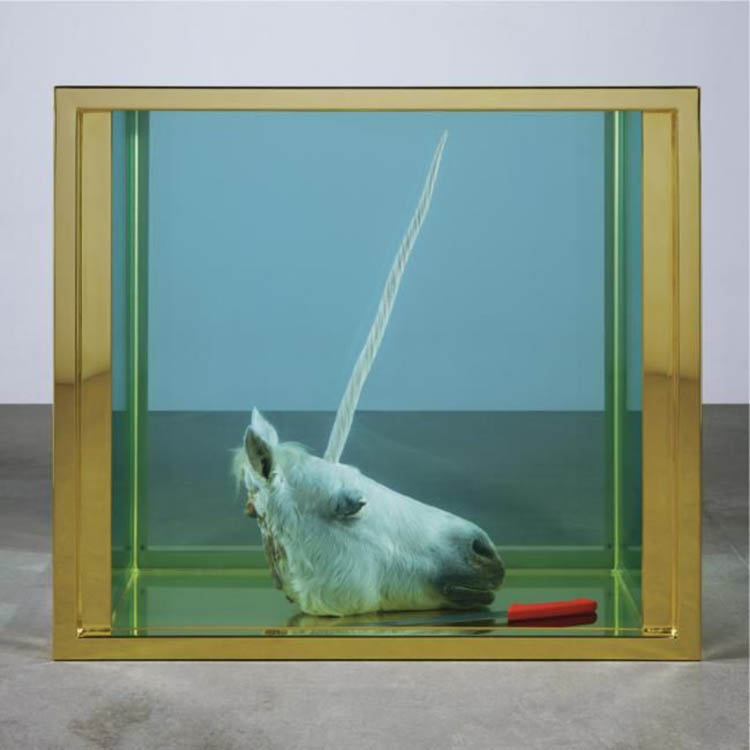

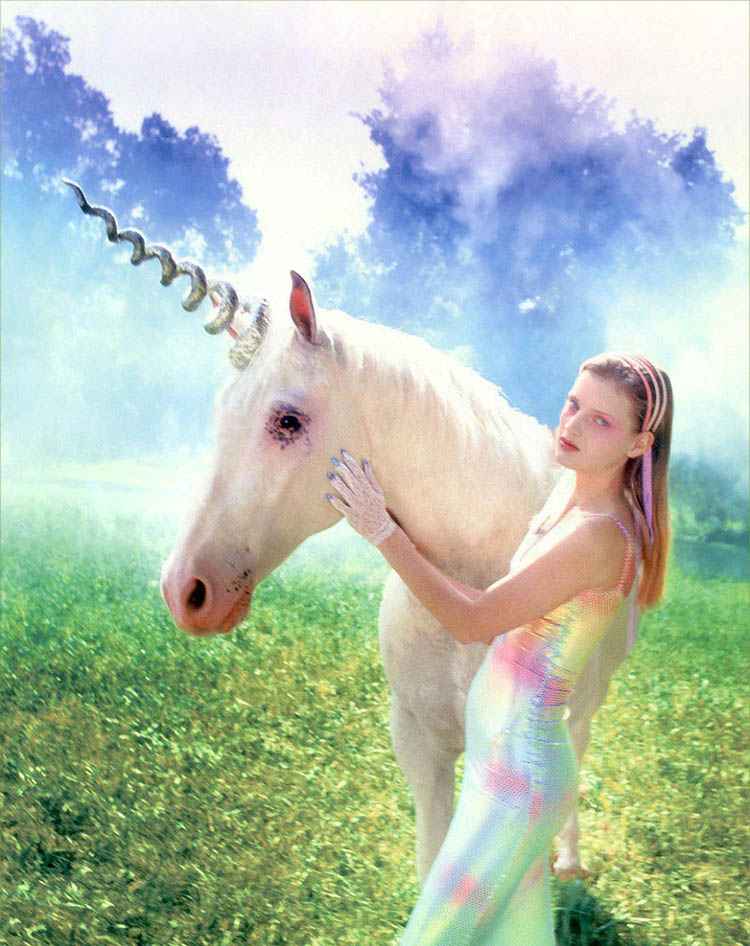

Today the unicorn is still used in many works of art, for example by famous photographer David Lachapelle (photo 13) or contemporary artist Damien Hirst (photo 12).

A strong heraldic symbol

All of these characteristics gave the unicorn a strong symbolic power to give off a sense of nobility and pureness, as well as courage and strength. It was thus widely used in fifteenth-century Europe by lords and knights who chose the unicorn for their coats of arms. Bartolomeo d'Alviano (1455-1515), the condottiere who worked for the Orsini family in Venice during the sixteenth century, had a coat of arms with a unicorn dipping its horn in a stream and a small text that read: “I chase away poison”.

The unicorn was also used as a symbol for entire kingdoms, such as that of Great-Britain, which was made of the English lion and the Scottish unicorn (photo 10), or of Canada, where the flag was adorned with a unicorn carrying the arms of France that Jacques Cartier planted. Cities also used it (Amiens and St Lô – see photo 11), as well as brotherhoods, like the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London.

This animal was therefore represented on all heraldic elements: war and parade objects such as flags and military equipment, as well as elements related to the lords' residences like sculpted low-relief architecture, fireplaces, and iron firebacks.

Bibliography

Édouard Brasey, La Petite Encyclopédie du merveilleux, Paris, Le pré aux clercs, September 14th, 2007.

Francesca Yvonne Caroutch, Le mystère de la Licorne: à la recherche du sens perdu, Dervy, 1997.

Jean Chevalier et Alain Gheerbrant, Dictionnaire des symboles, éditions Robert Laffont, coll. « Bouquins », 2005, « licorne ».

Christine Davenne, Modernité du cabinet de curiosités, L'Harmattan, coll. « Histoires et idées des arts », 2004.

Bruno Faidutti, Images et connaissance de la licorne : (Fin du Moyen Âge - XIXe siècle), Paris, November 30th, 1996.

Louis-Paul Fischer & Véronique Cossu Ferra Fischer, « La licorne et la corne de licorne chez les apothicaires et les médecins » (“The Unicorn and the unicorn's horn with apothicaries and doctors”), Histoire des sciences médicales, vol. 45, no 3, 2011, p. 265-274.

Margaret Freeman, La Chasse à la licorne : prestigieuse tenture française des Cloisters, Lausanne, Edita, 1983.

James Giblin (ill. Michael McDermott), The Truth about Unicorns, Harper Collins Publishers, 1991.

Pierre Malrieu, Le bestiaire insolite: l'animal dans la tradition, le mythe, le rêve, La Duraulié, coll. « Les Fêtes de l'irréel », 1987.

Guy de Tervarent, « Licorne », Attributs et symboles dans l'art profane – dictionnaire d'un langage perdu (1450-1600), Coll. Titre courant, Ed. Droz, Genève, 1997, p.281.