The andirons

Download PDFPlaced under the burning logs, andirons, or firedogs, allow the air to circulate under the wood and to fan the flames. An andiron consists of an iron bar on which the logs are placed, and a decorative head.

In French, they are called “chenets”, a noun coming from the word "dog", that refers to the role of this tool that keeps the fire, and their shape reminiscent of sitting dogs. That is why the English language also calls them "firedogs". It is also common to see andirons decorated with dogs lying or sitting, standing guard over the hearth, and more symbolically of the hearth of home. Perpetuating this idea, these dogs were sometimes replaced by lions, or sphinxes, for Marie Antoinette and under the Empire.

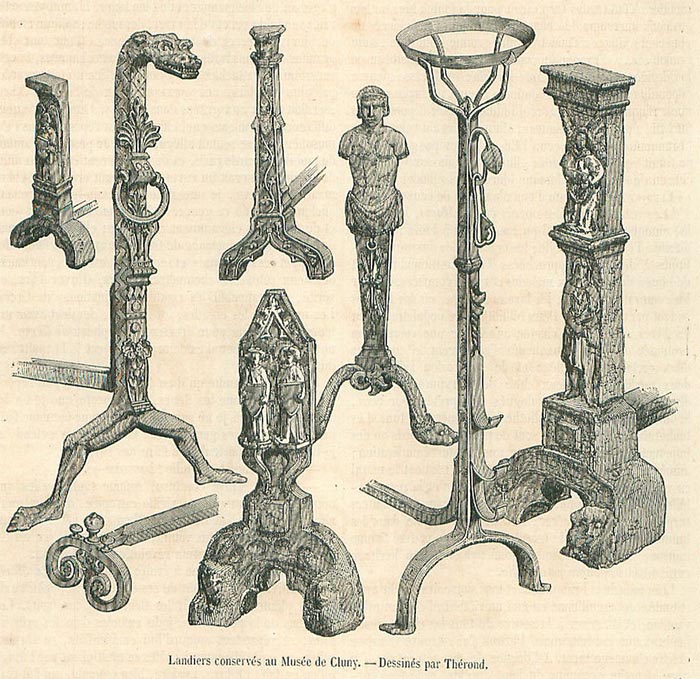

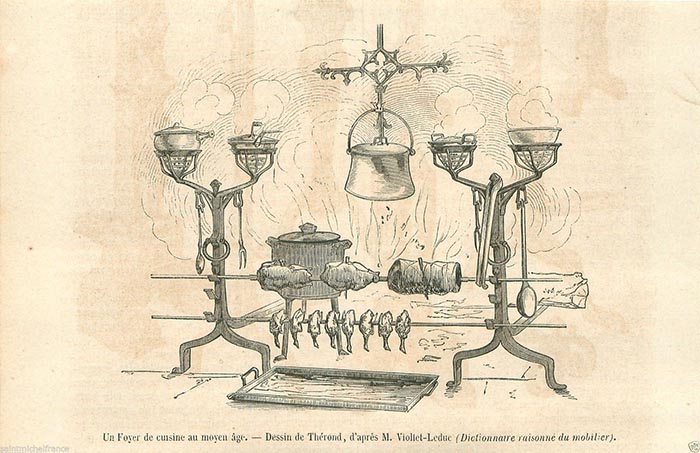

The utility of the andirons quickly became obvious. The ruins of Pompeii show that lifting fire on iron bars was already a known process in the Antiquity. In the Middle Ages, the andirons are very tall, as are the fireplaces, and are equipped in the kitchen with receptacles to keep dishes warm.

In the Renaissance they began to be made of bronze, which is lighter than iron. The Renaissance andiron is usually topped with a ball. Then, in the classical age, the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy of the seventeenth century were systematically equipped with andirons, often in copper. The decorative interest of the andirons developed under Louis XIII, where we see the appearance of silver andirons ordered by Cardinal Mazarin. Versailles Palace thus counted under Louis XIV some forty pair of silver firedogs, but they were melted to fuel the war effort of the Sun King.

The 18th century, true golden age of andirons, leaves out silver and brass to the benefit of gilt bronze. Like the rest of the interior decoration, the andiron is designed and redesigned by the great ornamentalists of the Louis XV and Louis XVI styles, to the extent that Versailles Palace and Trianon have a very wide variety of them.

The Louis XV style combines the flame-like shapes with the gilt bronze which gleams by the fire. The sinuous forms can sometimes be self-sufficient, but they often accommodate couples of animals or characters who respond, sometimes enhanced by a darker patina. On the andirons there are scenes of children's play, rest, gallantry or hunting. Jacques Caffiéri's Italian joyful temperament is fashionable and the fireplace becomes a place of conviviality and intimacy, with, for example, his pair of firedogs "Rooster" and "Hen" representing a gallant scene between two young people.

The Louis XVI style still uses these animals in complementary couples, such as the famous deer and wild boar andirons of Madame du Barry, designed by Quentin-Claude Pitoin in 1772. These animals, however, rest on symmetrical and ordered pedestals that characterize the andirons of the new trend adopted by Marie-Antoinette. Often decorated with vases and garlands, the andirons of the time revisit the forms of antiquity and also adopt sphinxes and chimeras. The models of Charles De La Fosse and the achievements of Pitoin and Pierre-Philippe Thomire dominate the period.

Rather than being designed in pairs, the andirons are sometimes mounted on a bar, which will often be used from the Empire. The nineteenth century largely reused the vocabularies of the eighteenth century, calling on the great sculptors of the time like Carrier-Belleuse or Feuchère, and great bronze makers like the Barbedienne Foundry.

But the firedogs, with their medieval name, also awaken the amateurs of the Neo-Gothic style. Thus, in the 19th century, many wrought iron andirons were built, inspired by the Middle Ages, with more or less fantasy. Eugène Grasset's end-of-the-century andirons kept in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris contribute to accentuate the mysterious charm that the space of the fireplace can have.

Bibliography

Alain Rey, Dictionnaire historique de la langue française, Robert, 1992, p. 735.

Raymond Lecoq, Les objets de la vie domestique : ustensiles en fer de la cuisine et du foyer des origines au XIXe siècle, Berger-Levrault, Paris, 1979.